Applying Geocaching Principles to Site-Based Citizen Science and Eliciting Reactions via a Technology Probe

Posted 23 Feb 2015

This is a piece of work that I was very excited to work on with Matthew A. Dunlap (officially, Tang 1), and Saul Greenberg, as it married one of Matthew’s interests (Citizen Science) with one of my personal interests at the time, Geocaching. For Matthew, it represents the culmination of his MSc efforts — a fairly lengthy haul that involved a lot of uncertainty and “We got scooped”‘s. For me, it followed on a series of papers with collaborators Carman Neusateder and Tejinder Judge that explored the mechanics of community and groupware in helping to maintain geocaching practice (Neustaedter, Tang, & Tejinder, 2010), and leveraging those lessons for the design of location-based games (Neustaedter, Tang, & Judge, 2013).

Main Idea

The main idea that Matthew explored was how we could leverage lessons from the design of geocaching, and apply those to aiding citizen science. Some terminology: Geocaching is a location-based treasure hunt game that takes place in the real world; citizen science is real science that involves untrained participants — often for the purpose of data collection (as in the classic “bird watch” project), and sometimes for analysis (as in the protein folding project). For instance, geocaching leverages known locations/sites paired with an online site — this allows people to find and revisit the site; this is something that can be leveraged by citizen science to allow for data collection, data verification (because people can revisit a site at a later time), and so forth. Matthew built a great little system called ScienceCaching to enable this style of citizen science, and got a lot of feedback from scientists engaged in citizen science. Overall, a pretty cool thesis.

##The Work Based on his literature survey and conversations with the citizen scientists (and people who managed citizen scientists), Matthew was able to identify four core problems faced by scientists trying to employ citizen science:

- Data collection. How can we ensure that data is collected in an error-free way? How can we enable real data collection that makes use of real tools?

- Data validation. How can we ensure the data should be trusted?

- Volunteer training. How can we train volunteers to ensure they are “good enough” to do some of this collection?

- Volunteer coordination. How do we ensure volunteer time is used effectively?

Matthew developed the idea of ScienceCaching to address these issues. For instance, Matthew’s prototype had a three-site “training” experience, where you need to find the site (part of the fun of Geocaching), and complete activities that are tracked using a mobile device (where the mobile device provides feedback on how “correct” you were). The prototype further shows the integration between the mobile device and a back-end that can be controled by a citizen science coordinator.

Beyond this, Matthew was able to develop and deploy this prototype several times to gather feedback from people involved in citizen science. To me, this was extremely valuable, as it revealed several basic ideas that we got wrong in ScienceCaching.

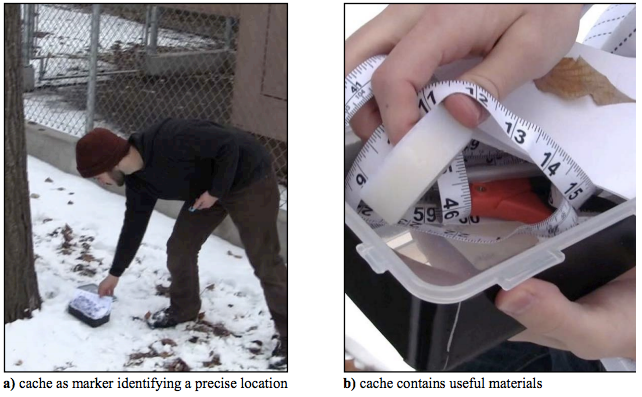

For instance, it turns out that citizen science volunteers are often involved in the activity for the social aspects of doing an activity with others (not just asynchronously via a website, but physically colocated activities with others!). This is something that can and should be leveraged in citizen science projects, and this was not something that we meaningfully addressed in the prototype. For instance, if we know that people are going out as a group, perhaps we can develop data collection activities that would otherwise be difficult/impossible if volunteers were going out on their own. Similarly, the scientists were excited about the prospect of using the caches as “physical specimen collection points” and places to store more advanced tools that would be difficult for volunteers to carry out into the field.

##Overall This was a really fun project to be involved in. I’m super happy that the work finally got published, as I think that ongoing citizen science projects can benefit from some of the lessons uncovered by Matthew. Saul seemed to enjoy it because it gave him a good opportunity to be outside. Haha!

Actually, he wanted me to add, “Saul enjoyed this opportunity to merge computer science with his passion for the outdoors and his gratitude for the many biologists who try to preserve it.”

##References

Carman Neustaedter, Anthony Tang, and Tejinder K. Judge. (2013). Creating scalable location-based games: lessons from Geocaching. Personal Ubiquitous Comput. 17, 2: 335–349. (journal).

Carman Neustaedter, Anthony Tang, and Judge K. Tejinder. (2010). The role of community and groupware in geocache creation and maintenance. In CHI ’10: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, ACM, 1757–1766. (conference).